Last year, I ran a session with high school students about startup pitches. The challenge was that students have so little background on how investors and startups work. That required too much lecture. This year, I want that background information to be available up front, letting the session be more hands-on.

What follows is an introduction to venture economics and startup pitching. This is based on a presentation, so I recorded the talk here, which you can read below.

Credentials

I studied computer science at NYU and robotics in grad school at CMU. I worked on bomb disposal robots at iRobot, before starting my first startup, backed by Y Combinator. I then worked in engineering at Facebook and product at Dropbox. My second startup was acquired by Lyft. My first angel investment was in Cruise Automation. I founded a new VC fund Tango.vc and just founded my third startup, Attention AI.

Types of Investors

Different types of people invest in startups.

Often founders will get friends and family to invest. They are low sophistication, investing their own money because they like you. The first concern is to make sure this unsophisticated buyer understands that startups are high variance and have a good chance to be worth nothing. The second concern relates to rules from the Securities and Exchange Commission, the SEC. In short, only take money from Accredited Investors, which essentially means having enough money to lose.

Angels are sophisticated but still investing their own money. They should already understand startups and their risks. They are almost certainly already Accredited Investors. The key difference between VC and Angels is investing other people’s money or your own money.

Venture Capitalists raise money from Limited Partners (LPs). They are limited because they have no say in day to day investing decisions. VCs have partnerships that decide how to invest. This means convincing a few people to invest. VCs will have a lot more money to invest than angels, so larger funding rounds focus there.

To understand what convinces VCs to invest, you need to understand the economics of their business. That means understanding carry, illiquid returns, and most especially power laws.

VC Economics: Carry

VCs make money in two ways. For assets under management (AUM) VCs earn a small percentage in a yearly fee, typically 2%. This pays salaries and other costs because startups take so long to pay off. VCs return cash or stock to LPs once the startups they backed go public or are acquired - years after the initial investment. VCs take 20% of the profits, called Carried Interest. “Carry” derives from shipping, where captains would take a profit share from goods they carried.

VC Economics: illiquid returns

If I lend you $100, how much should you expect back in a year? The US “Risk Free” rate for bonds backed by the US federal government and thousands of nuclear weapons is currently 3.88%. The bonds are liquid, as are other assets like public stocks, which means you can sell them at any time. The long term rate of return for the S&P 500 averages 7.38% after inflation.

Investments in startups are illiquid for years. This means the rate of return should be higher. This percentage growth yearly is called Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Over 10 years, IRR averages compound into a large multiple: 8% = 1.08^10 = 2.16X. 9% is 2.36X, and 10% is 2.59X.

This means a whole fund must return multiples of the original to justify the illiquidity.

Actually, many funds do much worse. The graph below shows the top and bottom quartile of fund IRR by the year the fund started, showing that some years the bottom funds return less than what was invested.

VC Economics: Powerlaw Returns

Each VC fund will make dozens of investments. But only a small share of those investments will impact the total returns. This isn’t intuitive because powerlaws don’t match a lot things in the world. One home on a block isn’t worth all the rest combined. One person in a crowd isn’t as tall as the rest combined. But for VC portfolios, it isn’t unusual for a single investment to be worth all the other investments out of the fund combined.

Let’s illustrate with an example. Accel invested $12.7M for 11% of Facebook in 2005, valuing the company at $115M. In 2010, they sold 20% of the stake at a $35B valuation worth $500M. $500M / 20% = $2.5B ~= 200 * $12.7M, meaning the investment already returned 200 times. In 2012, Facebook IPOed at $90B earned another $4B for Accel, totaling 350X. This means the original $440M Accel Fund IX returned 10X just from Facebook. 10^1/10 = 1.26, which means an IRR of 26% from this single investment. From the graph of fund distributions before, this single investment made the firm a top performer. It literally doesn’t matter what happened to all their other investments.

The fundamental conclusion here is that the very best investments a VC makes matter, but all the rest don’t. This means every single VC investment must have a chance to be the top.

See this illustrated here, where the fund on the left hit a bigger head of the powerlaw, but the fund on the right had fewer zeros, with more companies returning 1X or 2X. Fewer losers might seem better, but the fund with a better head of the powerlaw is worth twice as much.

To get VCs to invest, you need to convince them there is a chance your startup will be the best investment they ever make.

Startup Attributes

Because startups take years to take off, investors need to predict the distant future. The best evidence of future stellar performance is past performance, meaning traction to date. But what might predict more traction. Early on, you might just have an idea and the team. Here are the dimensions to consider.

Team: Who are the founders and early team members? Where have they worked or gone to school? What have they built in the past? Do they seem relentlessly resourceful?

Technology: What technology is required? Is it unique to the company? What work is ahead or already proven?

Market: How big is the market? How big will it be? How fast is it growing now? Is the current shape fragmented, a large incumbent, or something else?

Traction: Is your product available? How much money are you making? How many people are using it? Do they love it?

Go To Market: How will you reach your customers? How much will it cost? How fast can you grow? Who is the buyer? Are there regulatory hurdles?

Culture: What makes your company unique? How will you keep your culture strong?

Competition: Are there other players? Large or small? What advantages or disadvantages do they pose?

Why Now: What has changed that means your startup can succeed? Why have others failed before?

Bad Pitches

Here are some red flags to watch out for within these categories. If your startup suffers from them, try to solve the problem or at least have a good answer.

Team

🚩 No one technical

🚩 Everyone part time

Technology

🚩 Tacked-on trendy buzzwords, like AI or blockchain

🚩 Outsourced development

🚩 Hammer in search of a nail, like a grad student that just finished a thesis, looking for an application of the technology.

Market

🚩 Contingent growth where your customer growth isn’t guaranteed, like battery management for satellites

🚩 Substantial regulatory barriers

Traction

🚩 Shy or uninformed about metrics

🚩 Cumulative metrics. Always show rates of change

🚩 Graph manipulation, like compressing an x-axis to seem faster.

Go to Market

🚩 "We spent $0 on marketing" probably means you don’t understand the cost of different channels.

🚩 Modeling CAC decreasing substantially

🚩 Not metrics driven

🚩 Founders want to hire head of sales before establishing repeatable sales model. Symmetric with "no one technical"

Culture

🚩 Playing house

🚩 Not working long hours

🚩 Anything dishonest or low integrity

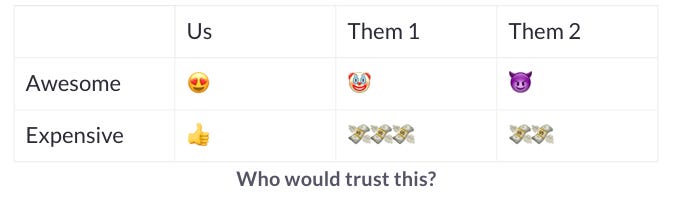

Competition

🚩 Inaccurately portraying your competition as hapless, unloved, and expensive.

There is a lot more to say about all this, but I hope this was a good introduction. In future posts, I’ll write in more depth about both VC economics and pitching.

Subscribe to get future posts.